Personal Finance 101 for Young Lawyers

Posted: Thu Jan 05, 2017 5:44 pm

Not sure if my own anecdotal selection of threads has led me to write this, but I continue to be dumbfounded as to how many people on here earning boatloads of money don't understand the very basics of personal finance. This is a super quick intro to help out young lawyers--hope it helps.

I. Random Terminology and Thoughts

II. Budgeting is Dumb...Just Lower Your Fixed Expenses

III. Hierarchy of Where Money Should Go

IV. A Brief Word on Taxes

V. Investing

VI. Contributing to Your 401k

VII. Pay Off Debt or Invest?

VIII. Student Loans

IX. Save for Retirement--It's Easier and Cheaper Than You Think

X. Conclusion

I. Random Terminology and Thoughts

Personal Finance is Personal: Before anything else, and I mention this a couple times, but personal finance is personal. You will see me shit on cars (I think they're dumb), talk about my risk aversion to buying a home, etc. Note that these are my personal opinions, and your situation might yield a different analysis.

Don't Become a Slave to a Spreadsheet: Another thing I've experienced--don't become so obsessed with money that you become a spreadsheet crazy personal finance fanatic. All of this info is so you can make conscious decisions about allocating your resources in the way you see most beneficial to your personal preferences and wants.

Anedoctal example: you'll read me advocate for early retirement and living on very low fixed costs below, and it's easy to picture me spending hours every month on a spreadsheet and living in a hut with no electricity. In fact, I live in a pretty modest house, I took a 10 day vacation out west this year (Montana, hiking around Mount Baker, and then Seattle), I went to two World Series games and the OSU-Michigan game this year (for the 15th consecutive year!), etc.

But I ruthlessly cut things I don't care about (e.g., cars, cable TV, etc.) to free up more resources to do these things. All of this information is so you can create your own personal efficiency. If you don't want a house and want nice cars, don't feel pressured to buy a big house--buy a modest house and drive around a Civic (or whatever). If you want to travel to Europe instead of my less expensive vacation, go for it. Just make conscious decisions.

Adjusted Gross Income This is your income minus specific and usually tax-advantaged deductions, such as a student loan interest deduction, traditional IRA contributions, 401k contributions, etc. You should always try to maximize income while minimizing AGI, especially if you are on an income driven repayment plan.

Uncertainty: A basic goal of personal finance is to reduce risk. Like it or not your income will not just go up and up and up. Things will change (e.g., kids, spouse's unemployment, bad year at the firm, etc.). I know a partner at a huge firm in Cleveland who saw an enormous reduction in income the year they merged with another big firm. You need to create a plan for this to happen.

Renting vs. Buying: There are a ton of factors to consider, but you should only buy if you think you will live there for seven years or more (assuming 30 year mortgage). The rest depends on your location and you should Google "New York Times Rent vs. Buy calculator" to see what the costs are like. I will also briefly note that the mortgage deduction is a steaming pile of shit to trick people into buying more expensive homes and, thus, you should not buy a $500k home to save a couple grand on taxes for the same reason you shouldn't buy some super outrageous purchase at Best Buy just because it's 10% off.

Pre-Tax vs. Post-Tax: I generally prefer pre-tax investing because I hate taxes and figure I will be in a lower tax bracket when I retire. A traditional IRA is pre-tax contributions and then you pay tax on it later; a Roth IRA involves post-tax contributions and you do not have to pay tax when you pull the money.

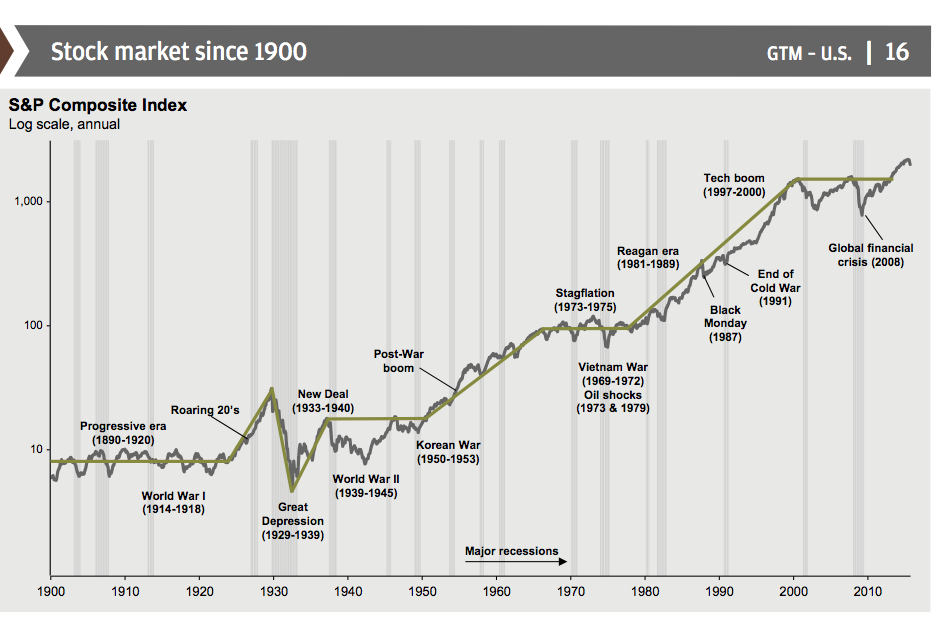

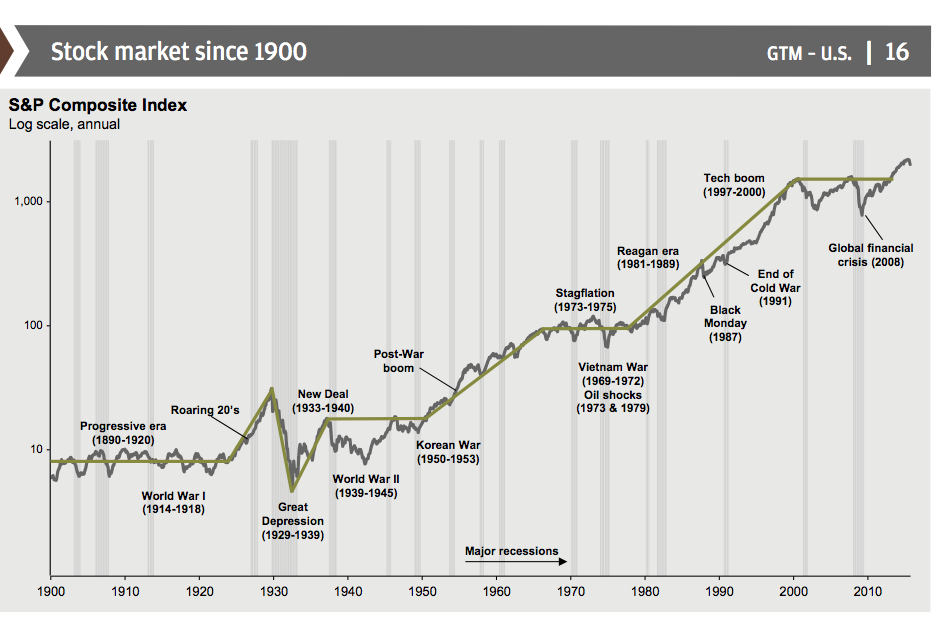

Stock Market: The stock market, over the long run, earns about 7%. Don't be afraid of dips.

Live Below Your Means: The lower you live below your means, the more you can save. The more you can save, the more you can invest. The more you can invest, the sooner you can retire.

Forget Everything You Thought You Knew About Retirement: Speaking of retirement, there is no greater bullshit lurking in personal finance world than retirement. It's not hard and you don't need a lot of money, and yes, you can pull money from pre-tax accounts without paying a bunch of penalties. More on that later.

So onto a few things.

II. Budgeting is Dumb...Just Lower Your Fixed Expenses

Generally: "Budgeting" implies guilty feelings. "Ugh I can only spend $100 on going out this month cause of my budget." Please. That's bullshit.

I do not have a budget, I have a spreadsheet averaging out my expenses so I know how much everything costs. Some costs are the same every month (e.g., cell phone bill), while others are variable (e.g., electricity bill, groceries). All of these necessary expenses are "fixed monthly costs," and you should seek to lower them as much as possible. Keep track of these for a year so you really know how much everything is, because almost everyone underestimates what they actually spend on their necessary expenses (much the same way people underestimate how much they eat).

In other words, don't worry about arbitrary categories like "$50 for electricity; $100 for dining out; $100 for social; etc." Just track your expenses so you know where your money is going, and make sure you are satisfied with the decisions you are making.

Focus on Small Wins After You've Tackled Big Wins: Too much personal finance advice focuses on small wins like "don't buy lattes and you'll have $1,000 by the end of the year." That's all well and good but they pale in comparison to "big wins." For example, if you're in NYC, you can save $1,500 a month by living with a roommate or two. You can also seek to increase income, do something on the side, and earn more money (if you have time). This, again, would likely be of more benefit than stressing incessantly about small things.

This isn't to say you should just piss away money at Dunkin Donuts every morning. Small things add up very quickly if they are habitual. But make sure you are making conscious decisions about these things, and more importantly, I think more time should be focused on thinking about rolling monthly expenses and achieving big wins.

Reduce Rolling Monthly Expenses: Once you figure out where money is going, absolutely and positively reduce fixed monthly costs as much as possible--even if you are making $160k. Reducing fixed costs increases cash flow, lowers the amount you need in your emergency fund, and in itself acts as a sort of self-insurance against the inevitable shit hitting the fan. Some thoughts:

Rent/Mortgage: live with a roommate or two, or your spouse. This is a huge win, especially if you are in a high COL area.

Utilities: again, live with someone so you can divide these. Be mindful about water and electricity--I've saved like 30% just from paying attention to when shit is on or off.

Cell Phone: you need less data than you probably have. Call your cell phone company and get on a plan around $50. Better yet ask your employer (HR) if they will reimburse you for your cell phone.

TV: I'm a crazy sports fan that doesn't have cable. I use antenna and Sling, and also have Netflix. I went from $117/month with cable to $31/month with Sling. Life's good.

Car/Gas: Just my opinion, but (a) cars are crazy stupid and a laughable waste of money given their utility; (b) you don't deserve a nice new car just because you got a real job; and (c) most of the "congratulations!" you get when you buy a new car are from consumerist idiots. Sure, you can get a new car when the time is right, but don't jump the shark just because you got a new job. I have friends with CRAZY car payments ($550/month) because they wanted to reward themselves and didn't take the time to save. Saving for a down payment = lower monthly payment = lower fixed costs = more to invest per month. As with everything else, this is a trade-off, but make a conscious plan based on where you find utility.

Low Fixed Costs = More to Invest: Your money can work harder than you can. This is totally random and anecdotal and you should not taken it as any definitive proof of anything, but my 401k made $637 yesterday doing absolutely nothing. That's more than I made yesterday actually working. Years from now, that money will produce a comical amount in a single day when the stock market goes up .5% in a day.

So go read about compound interest and how crazy powerful it is. I could go on and on, but you get the point--lower fixed costs is a great idea.

III. Hierarchy of Where Money Should Go

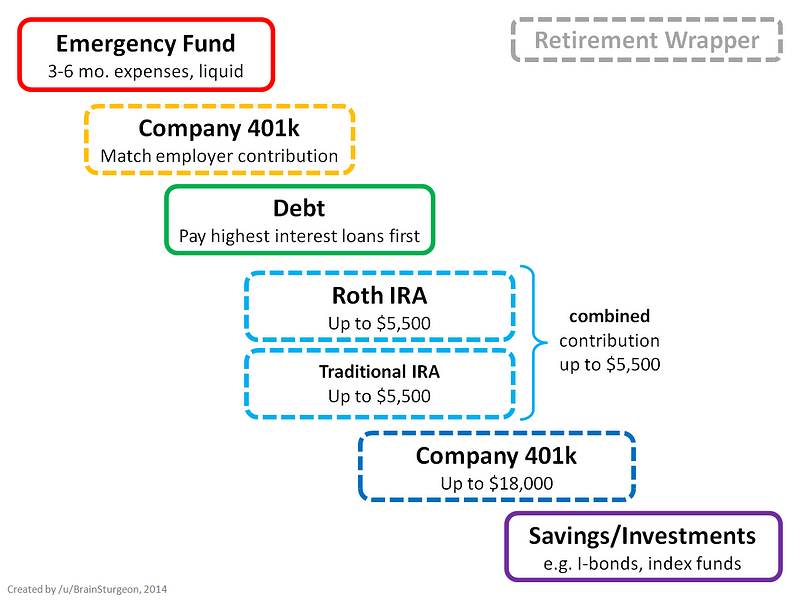

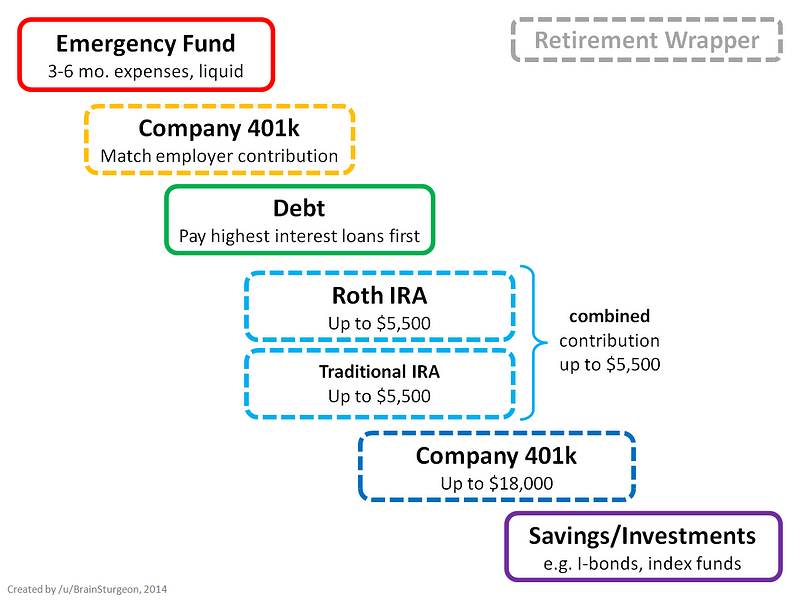

The basic premise of this hierarchy is where to put money after expenses. If you have a lot left over, you should be able to do all of the below; if you don't, no big deal, work your way down the hierarchy and you will be ahead of 80% of people. This is a fun graphic summary from r/personalfinance (which is a great reference):

1. Emergency Fund: first thing to do is have liquid cash available in case shit hits the fan. Most people I read recommend 3-6 months of fixed expenses, or basically, enough liquid money to get you through something unexpected. Young people don't think this will happen to them, because we are young and awesome and smarter than boomers. But my fiance had her gallbladder almost burst two years ago and it cost about $6k.* That's why you have an emergency fund.

*Poor girl can't eat fried food anymore. Sigh.

Also note that, if you have kids, 3-6 months of expenses should account for them and any emergencies they might have. I personally like having 3 months of fixed expenses plus enough to cover my insurance deductibles.

I would recommend just keeping this in your checking account, but if you are too impulsive, open an account at Ally. They pay 1% interest on your money, which doesn't sound like a lot, but we have $10,000 in our Ally account and thus get a free $100 every year without doing anything (that's basically free Netflix for 10 months). I figure/hope these interest rates should go up, too, so eventually these will pay a bit better.

In short, though, keep this in purely liquid form (checking or savings account) so you don't have to fuck around to get your money.

2. 401k up to Match: Contribute to your 401k up to the company match. This is free money and is a 100% return on your money. Do it even if you have $30 billion in student loan debt.

3. Pay Off High Interest Debt: Pay off debt that has a high interest rate (I'd say 6% or higher). This is complicated with student loans (I'll discuss below), but if you have a car loan with a dumb interest rate, or especially credit card debt, pay that off ASAP.

4. Max HSA Contributions: An HSA is a Health Savings Account. Unlike most other tax-advantaged accounts, the contributions (what you put in) AND withdrawals (what you take out) are pre-tax. It's basically 100% tax free money. Contribute to it and use it whenever you have a health-related expense. Some decent anecdotal examples:

I just bought new frames and glasses and used my HSA. This was pre-tax in its contribution and withdrawal. It thus cost me just $110 FLAT to buy these. If I needed to use post-tax money, it would have cost about $150 in actual pre-tax income, then have taxes taken out, to have that much in cash.

Again, I'm big into pre-tax investments as much as possible.

Make sure, however, that you check (a) state laws and (b) your health plan to see if you can access an HSA. Talk to HR about this.

Random Anecdotal Opinion: Because of the above, I actually find myself actually taking care of myself with preventative care. It feels a lot better to go get your physical, go to the dentist, go to the dermatologist, etc. when you are using pre-tax money. This might be one of those mind tricks, but it works for me. Hopefully someone else writes a thread about health/wellness because I could still use a few pointers there.

5. Max IRA: This is tricky because of income levels and tax brackets. If you are in Big Law then skip to #6. If you make less than $71,000 then contribute the max ($5,500) to a traditional IRA. Traditional IRA is better than 401k because there are usually less admnistrative fees and you have a wider variety of funds from which to select.

There is a big debate about contributing to a Roth (post-tax) or Traditional IRA (pre-tax). Google "Roth vs. Traditional IRA" and read about it and select from your personal preferences. All I'll say is that I prefer pre-tax investing because I anticipate paying little to almost no taxes in retirement.

6. Max 401k: Max your 401k up to the full $18,000 (if you can). I personally find this to be a great way of saving because the money is taken directly from your paycheck, put into your 401k, and then it's relatively hard to get. Do this.

7. Pay Off Lower Debts: This is disputable with #8, but I'd pay off lower debts next. Paying off a debt with a 3-4% interest rate means you are getting an automatic rate of return slightly above that number. Reducing debt reduces fixed costs, which you can tell I like.

8. Taxable Brokerage Account: This is last because with contributions invested post-tax, the gains (i.e., the amount earned on the investments) are taxed as capital gains. But even with this, you are better off investing than leaving too much money on the side (i.e., uninvested).

IV. A Brief Word on Marginal Taxes

Taxes Are Marginal: A lot of people screw this up. Taxes are marginal. This means that your tax rate is the percentage of tax applied to your income for each tax bracket in which you qualify. It breaks down like so:

In word terms, this means that income between $0 and $9,275 is taxed at 10%. Income between $9,276 and $37,650 is taxed at 15%. And so on.

You want to contribute to pre-tax accounts so you can lower your AGI and thus lower your tax burden.

Easy example: You make $160k in Big Law. The last $18,000 of that is taxed at 28%. Contribute all of that money to a 401k instead and boom, you have all $18,000 of that money invested; conversely, if you invested none of that, $5,040 would have been taxed, and you go home with $12,960. That sucks. Invest the whole damn thing and win.

Note that some people confuse this whole "marginal tax" thing. They think, "If I go from $75k income to $100k, now I'm in the 28% tax bracket and I'll make less." Now you can look at them and laugh because you read on the internet that this is complete bullshit. Almost all of the income will be taxed the same, just the income from $91k to $100k will be taxed at 28%. And if you contribute to your 401k, you will avoid that higher marginal tax rate! BOOM!

V. Investing

Invest in Stocks, They Always Go Up: This might catch some flack, but given a long enough time horizon, stocks always go up. All the noise you hear about the market is complete and total bullshit. There's a really important saying you must burn into your brain: time in the market beats timing the market. See below.

This is one of my favorite articles ever--what would happen to a guy who always invested at market peaks (i.e., pre-collapse): http://ritholtz.com/wp-content/uploads/ ... e-1900.png.

Point is that you should always just continuously invest. Do not pull out of the market just because of a recession--look at the chart above, the market always comes back up (just as it did after 2008, just as it did after the mini-bear blip early in 2016).

You should be 90/10 (or maybe 100) percent in stocks/bonds until you are about five years from retirement. Then it might be time to see an adviser.

Invest Passively in Index Funds: An index fund is a fund that tracks an index and nothing else (e.g., the Dow, the NYSE, the S&P 500). Do this for several reasons:

1. These are extremely low cost. Costs are important. Costs kill your returns in the long run.

2. You cannot beat the average. People get paid hundreds of thousands of dollars per year as their full time job, and they usually don't beat the market.

This is anecdotal, but given it's the new year, check this out: http://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/04/upsho ... ctionfront

TL;DR: none of the professional's "stocks to buy in 2016" beat the market. You can't beat it either. It's okay to have, say, 5-10% of your money as "haha I'm gonna play with stocks," but any more than that is dumb.

Costs Are Super Important: Index funds have super low costs. Let's look at an example:

Fund A: an actively managed fund that gets 8% returns (better than the market average) but has a 1.75% expense ratio. If you invest $10,000 per year for 30 years, minus fees, you end up with $877k.

Fund B: a passive index fund with 7% returns (market average), with an expense ratio of .05% (which is what mine is). If you invest $10,000 per year for 30 years, minus fees, you end up with $1.01M.

Thus, even if Fund A did better, because of its fees, it ate up more than $125k in returns. This is because fees compound just like returns do.

But wait, there's more. This hypothetical assumed that actively managed Fund A outperformed the market average over 30 years--this does not happen at a rate of about 98% of the time when it comes to active vs. passive funds. In other words, 98 out of 100 active funds fail to beat passive funds over the course of 30 years.

Thus, Fund A, at best, likely had 7% (average) returns, but subtract costs and you have $730k. Now you've lost a quarter million because of fees.

Fees, over time, kill performance. Avoid them, and because of this same principle, avoid financial advisers (unless you have a crazy complicated financial situation, which, in that case, hire a fee only financial adviser that is a fiduciary).

Time in the Market Beats Timing the Market: I'm going to repeat this for emphasis: invest as long as you can, because compound interest is awesome. Let's look at another example.

Person A graduates law school and, at age 25, begins investing $15,000 per year for 20 years (contributions total $300,000). He stops contributions at age 45 (for whatever reason) and lets his money grow to age 60 without withdrawing any funds. Assuming 7% returns, Person A has $1.8M at age 60.

Person B graduates law school and lives the dream, but does not contribute until age 35. He then contributes $18,000 per year from age 35 to 60 (contributions total $450,000). Despite investing substantially more, and again assuming 7% returns, Person B has $1.1M at age 60.

Rules to Remember: Contribute as early and as much as possible. Reinvest your dividends. Invest in low cost index funds. Invest mostly in stocks.

Additional Reading on Investing:

http://jlcollinsnh.com/stock-series/

https://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/Boglehe ... philosophy

VI. Contributing to Your 401k

Basics: A lot of this is covered in the investing section above, but if you're in Big Law, I can't imagine not contributing all $18k to my 401k. I make 1/3 of Big Law salary and contribute the full $18k--you can too (if you lower your fixed expenses enough).

Within your 401k, select index funds with low expense ratios. I'd recommend the S&P 500 index, which tracks the 500 biggest companies in the U.S. Some suggest investing in international indexes, but I agree with John Bogle that American companies have international exposure and thus ebb and flow with those markets anyway.

Always Roll Over Your 401k: You will likely switch jobs within five years. Never, ever, cash this money out (unless you are in a dire emergency). See "time in the market" principle.

VII. Pay Off Debt or Invest?

This is Likely Personal: This is a super tricky topic that deserves its own article. Before getting into my belief, just note that personal finance is personal. Some people (me) are totally okay with debt, others despise it and want to get rid of it. You do you.

Focus on the Interest Rate: The number one factor to consider in whether to pay off debt or invest is what interest rate your debt is. Always remember as a baseline that the stock market has returned (over the long run) about 7% after inflation. If your debt is much lower than this (3-4%), let the debt ride and invest, because your investments, over the long term (and with the power of compound interest) will beat the "returns" of paying off lower interest debt.

Conversely, if it's high interest debt (e.g., a credit car with 18% interest), get rid of that ASAP. That is terrible debt and investing will never beat this type of debt. Note that you should contribute to your 401k before paying off this debt, because 401k up to your company's match is a 100% return, which beats the interest rate on your debt.

Student Loans: Note here, and I'll discuss below, that student loans are different due to income driven repayment plans. This makes the interest rate on student loans borderline fake. You really need to do a case by case analysis.

VIII. Student Loans

Get on An Income Driven Repayment Plan: I don't care whether you're in small law (me) or big law, get on REPAYE. Its provisions include allowing your payments to go to $0 if hardship arises. This is basically student loan insurance.

Don't Refinance Unless You're Sure You Will Pay Them Off Soon: Refinancing takes away the above insurance. It also usually involves a co-signer, which means that if you die, they can go after your spouse. Not good. Again, federal loans have built in insurance-type protections in them. This makes their slightly higher rates worth it.

Gaming Student Loans: This is a borderline fetish topic for me because I've looked into it almost a laughable amount. But basically, if you make low income, get on REPAYE, intentionally lower AGI, and never plan on repaying your loans back in full. You will almost certainly pay less if the numbers work out right (e.g., lower income, high debt; or even high income with a lot of contributions reducing AGI). This is complicated, and deserves an entirely separate post, but make sure you look into REPAYE before becoming one of those people who makes paying off loans a higher priority than sex.

IX. Save for Retirement--It's Easier and Cheaper Than You Think

This is Personal!: What you are about to read is my own thoughts on retirement. But basically, as you'll see, I'm aiming for a modest standard of living so I can retire early, because I value time and I don't really aspire for material/costly stuff--I don't really care about having a huge house, a Mercedes, sending my kids to private school, etc. It's just not important to me. Of course, some of you went to elite undergrad and elite law schools and now are in big law so you can aim higher than that. This is perfectly fine. You're not wrong, I'm not right. Just know that your standard of living and current spending drastically affects if and when you can retire.

Money Buys Time: I could go on a long rant here, but money can be used as a utility for one of two things: (1) to buy stuff (houses, cars, food, etc.) or (2) time (a retirement fund). I personally place higher utility in time, not consumerist stuff. Read "Your Money or Your Life" for more on this.

How Much Do You Need: This is perhaps the dumbest thing going in mainstream personal finance. Professionals who do finance for a living honest to God think that $2M isn't enough. That's laughable.

Here's the key: assuming no income (social security, retirement hobby, etc.), you need 25 times your yearly expenses to retire. I conservatively project that my fiance and will spend about $48,000 per year (assumes a paid off mortgage), meaning we need $1.2M to retire. Because we are maxing our accounts, I think we will get there at age 42-45.

If you think this isn't a lot, go read Mr. Money Mustache--he retired in $625,000 and is killing it because his expenses are so damn low.

Where Does 25x Expense Come From?: This number comes from the fact that, statistically speaking, if you only pull 4% from your retirement accounts, they will last forever. This is because, over time, stocks go up at 7%, inflation goes up by 3% (and thus eats 3% of returns), leaving you with a gap of 4% to spend reliably, forever. That's oversimplified, but I'll point you to this article: http://www.mrmoneymustache.com/2012/05/ ... etirement/

The following graphic shows the power of savings rate--the higher percentage of income you save (savings rate), the less years you need to work:

Important Note: If you want a higher standard of living in retirement, that's fine! Go for it! This is a purely personal value trade-off in which you are basically agreeing to work more to have a higher standard of living in retirement. That is an entirely okay decision and is a completely rational trade-off to make. So long as you are aware of this when you are making big decisions (e.g., buying an expensive car, an expensive house, etc.), you will go a long way in knowing how much you are going to need for retirement.

If You're in Big Law--Save Like Crazy: I don't have the stomach for Big Law, but God I wish I did. With spousal income I'd save $125k per year. You would have close to $2M after 10 years. That's plenty to retire on if you're smart.

Retirement Does Not Mean Not Working: There is a societal retirement police. You are supposed to retire at a certain time, with a certain amount of money, at a certain stage of your life, and damnit you better not work AT ALL during retirement. All of this, much like other societal norms, is complete and total bullshit (this has to be the 10th time I've said that this post...who cares...emphasis matters).

I personally plan to "retire" at age 42-45. If I haven't started a solo practice by then, I might try that. I also might try to become a mediator and try to mediate 10-20 cases per year for some income. I'd also like to become a coordinator for a local high school football team (serious).

The better term here, I guess, is financial independence, or what some call fuck you money--having enough money so you can do whatever the hell you want with your time. This seems extremely ideal to me, so I'm aiming for it as soon as possible.

How to Access Money: You likely notice I discussed contributing mostly to retirement accounts, which you usually can't pull from until you are 59.5. Some might ask, "How do I get the money?" This is more complicated than intended for this post, but google Roth IRA conversion ladder, 72(t) distributions, and other ways to get this money. It's definitely advanced but it's possible.

X. Conclusion and Further Reading

This got pretty anecdotal towards the end, but I'm at work and a 30 minute lunch break turned into a two hour post. I know some people will disagree with my personal opinions, but I hope the value provided here outweighs any of that. Overall, to summarize what I think is universal advice:

1. Have an emergency fund of 3-6 months of expenses;

2. Follow the hierarchy of where your money should go;

3. Invest in low cost index funds;

4. Save as much as possible;

5. Make choices that parallel your personal comforts re finances (e.g., comfort with debt);

6. Understand that higher cost of living = you need more to retire; and

7. Educate yourself.

Personal finance and accumulating wealth is fun, and admittedly nothing I'm saying is really original--most of it is from years of reading blogs, r/personalfinance, r/financialindependence, and forums at Bogleheads and Mr. Money Mustache. I'd recommend the following:

Books

1. I Will Teach You to be Rich (https://www.amazon.com/Will-Teach-You-B ... o+be+reach)

2. Your Money or Your Life (https://www.amazon.com/Your-Money-Life- ... 6MGKDSFXCR)

3. Bogleheads' Guide to Investing -- good shit on insurance, other adult shit (https://www.amazon.com/Bogleheads-Guide ... 2QZZMTTGA1)

4. The Little Book of Common Sense Investing (https://www.amazon.com/Little-Book-Comm ... ME3FQGE8SB)

5. A Random Walk Down Wall Street (https://www.amazon.com/Random-Walk-Down ... JZH5D32HRT)

Websites

1. http://www.iwillteachyoutoberich.com/blog/

2. http://www.mrmoneymustache.com/ (A very alternative viewpoint to mainstream personal finance)

3. https://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/Main_Page

Cheers.

I. Random Terminology and Thoughts

II. Budgeting is Dumb...Just Lower Your Fixed Expenses

III. Hierarchy of Where Money Should Go

IV. A Brief Word on Taxes

V. Investing

VI. Contributing to Your 401k

VII. Pay Off Debt or Invest?

VIII. Student Loans

IX. Save for Retirement--It's Easier and Cheaper Than You Think

X. Conclusion

I. Random Terminology and Thoughts

Personal Finance is Personal: Before anything else, and I mention this a couple times, but personal finance is personal. You will see me shit on cars (I think they're dumb), talk about my risk aversion to buying a home, etc. Note that these are my personal opinions, and your situation might yield a different analysis.

Don't Become a Slave to a Spreadsheet: Another thing I've experienced--don't become so obsessed with money that you become a spreadsheet crazy personal finance fanatic. All of this info is so you can make conscious decisions about allocating your resources in the way you see most beneficial to your personal preferences and wants.

Anedoctal example: you'll read me advocate for early retirement and living on very low fixed costs below, and it's easy to picture me spending hours every month on a spreadsheet and living in a hut with no electricity. In fact, I live in a pretty modest house, I took a 10 day vacation out west this year (Montana, hiking around Mount Baker, and then Seattle), I went to two World Series games and the OSU-Michigan game this year (for the 15th consecutive year!), etc.

But I ruthlessly cut things I don't care about (e.g., cars, cable TV, etc.) to free up more resources to do these things. All of this information is so you can create your own personal efficiency. If you don't want a house and want nice cars, don't feel pressured to buy a big house--buy a modest house and drive around a Civic (or whatever). If you want to travel to Europe instead of my less expensive vacation, go for it. Just make conscious decisions.

Adjusted Gross Income This is your income minus specific and usually tax-advantaged deductions, such as a student loan interest deduction, traditional IRA contributions, 401k contributions, etc. You should always try to maximize income while minimizing AGI, especially if you are on an income driven repayment plan.

Uncertainty: A basic goal of personal finance is to reduce risk. Like it or not your income will not just go up and up and up. Things will change (e.g., kids, spouse's unemployment, bad year at the firm, etc.). I know a partner at a huge firm in Cleveland who saw an enormous reduction in income the year they merged with another big firm. You need to create a plan for this to happen.

Renting vs. Buying: There are a ton of factors to consider, but you should only buy if you think you will live there for seven years or more (assuming 30 year mortgage). The rest depends on your location and you should Google "New York Times Rent vs. Buy calculator" to see what the costs are like. I will also briefly note that the mortgage deduction is a steaming pile of shit to trick people into buying more expensive homes and, thus, you should not buy a $500k home to save a couple grand on taxes for the same reason you shouldn't buy some super outrageous purchase at Best Buy just because it's 10% off.

Pre-Tax vs. Post-Tax: I generally prefer pre-tax investing because I hate taxes and figure I will be in a lower tax bracket when I retire. A traditional IRA is pre-tax contributions and then you pay tax on it later; a Roth IRA involves post-tax contributions and you do not have to pay tax when you pull the money.

Stock Market: The stock market, over the long run, earns about 7%. Don't be afraid of dips.

Live Below Your Means: The lower you live below your means, the more you can save. The more you can save, the more you can invest. The more you can invest, the sooner you can retire.

Forget Everything You Thought You Knew About Retirement: Speaking of retirement, there is no greater bullshit lurking in personal finance world than retirement. It's not hard and you don't need a lot of money, and yes, you can pull money from pre-tax accounts without paying a bunch of penalties. More on that later.

So onto a few things.

II. Budgeting is Dumb...Just Lower Your Fixed Expenses

Generally: "Budgeting" implies guilty feelings. "Ugh I can only spend $100 on going out this month cause of my budget." Please. That's bullshit.

I do not have a budget, I have a spreadsheet averaging out my expenses so I know how much everything costs. Some costs are the same every month (e.g., cell phone bill), while others are variable (e.g., electricity bill, groceries). All of these necessary expenses are "fixed monthly costs," and you should seek to lower them as much as possible. Keep track of these for a year so you really know how much everything is, because almost everyone underestimates what they actually spend on their necessary expenses (much the same way people underestimate how much they eat).

In other words, don't worry about arbitrary categories like "$50 for electricity; $100 for dining out; $100 for social; etc." Just track your expenses so you know where your money is going, and make sure you are satisfied with the decisions you are making.

Focus on Small Wins After You've Tackled Big Wins: Too much personal finance advice focuses on small wins like "don't buy lattes and you'll have $1,000 by the end of the year." That's all well and good but they pale in comparison to "big wins." For example, if you're in NYC, you can save $1,500 a month by living with a roommate or two. You can also seek to increase income, do something on the side, and earn more money (if you have time). This, again, would likely be of more benefit than stressing incessantly about small things.

This isn't to say you should just piss away money at Dunkin Donuts every morning. Small things add up very quickly if they are habitual. But make sure you are making conscious decisions about these things, and more importantly, I think more time should be focused on thinking about rolling monthly expenses and achieving big wins.

Reduce Rolling Monthly Expenses: Once you figure out where money is going, absolutely and positively reduce fixed monthly costs as much as possible--even if you are making $160k. Reducing fixed costs increases cash flow, lowers the amount you need in your emergency fund, and in itself acts as a sort of self-insurance against the inevitable shit hitting the fan. Some thoughts:

Rent/Mortgage: live with a roommate or two, or your spouse. This is a huge win, especially if you are in a high COL area.

Utilities: again, live with someone so you can divide these. Be mindful about water and electricity--I've saved like 30% just from paying attention to when shit is on or off.

Cell Phone: you need less data than you probably have. Call your cell phone company and get on a plan around $50. Better yet ask your employer (HR) if they will reimburse you for your cell phone.

TV: I'm a crazy sports fan that doesn't have cable. I use antenna and Sling, and also have Netflix. I went from $117/month with cable to $31/month with Sling. Life's good.

Car/Gas: Just my opinion, but (a) cars are crazy stupid and a laughable waste of money given their utility; (b) you don't deserve a nice new car just because you got a real job; and (c) most of the "congratulations!" you get when you buy a new car are from consumerist idiots. Sure, you can get a new car when the time is right, but don't jump the shark just because you got a new job. I have friends with CRAZY car payments ($550/month) because they wanted to reward themselves and didn't take the time to save. Saving for a down payment = lower monthly payment = lower fixed costs = more to invest per month. As with everything else, this is a trade-off, but make a conscious plan based on where you find utility.

Low Fixed Costs = More to Invest: Your money can work harder than you can. This is totally random and anecdotal and you should not taken it as any definitive proof of anything, but my 401k made $637 yesterday doing absolutely nothing. That's more than I made yesterday actually working. Years from now, that money will produce a comical amount in a single day when the stock market goes up .5% in a day.

So go read about compound interest and how crazy powerful it is. I could go on and on, but you get the point--lower fixed costs is a great idea.

III. Hierarchy of Where Money Should Go

The basic premise of this hierarchy is where to put money after expenses. If you have a lot left over, you should be able to do all of the below; if you don't, no big deal, work your way down the hierarchy and you will be ahead of 80% of people. This is a fun graphic summary from r/personalfinance (which is a great reference):

1. Emergency Fund: first thing to do is have liquid cash available in case shit hits the fan. Most people I read recommend 3-6 months of fixed expenses, or basically, enough liquid money to get you through something unexpected. Young people don't think this will happen to them, because we are young and awesome and smarter than boomers. But my fiance had her gallbladder almost burst two years ago and it cost about $6k.* That's why you have an emergency fund.

*Poor girl can't eat fried food anymore. Sigh.

Also note that, if you have kids, 3-6 months of expenses should account for them and any emergencies they might have. I personally like having 3 months of fixed expenses plus enough to cover my insurance deductibles.

I would recommend just keeping this in your checking account, but if you are too impulsive, open an account at Ally. They pay 1% interest on your money, which doesn't sound like a lot, but we have $10,000 in our Ally account and thus get a free $100 every year without doing anything (that's basically free Netflix for 10 months). I figure/hope these interest rates should go up, too, so eventually these will pay a bit better.

In short, though, keep this in purely liquid form (checking or savings account) so you don't have to fuck around to get your money.

2. 401k up to Match: Contribute to your 401k up to the company match. This is free money and is a 100% return on your money. Do it even if you have $30 billion in student loan debt.

3. Pay Off High Interest Debt: Pay off debt that has a high interest rate (I'd say 6% or higher). This is complicated with student loans (I'll discuss below), but if you have a car loan with a dumb interest rate, or especially credit card debt, pay that off ASAP.

4. Max HSA Contributions: An HSA is a Health Savings Account. Unlike most other tax-advantaged accounts, the contributions (what you put in) AND withdrawals (what you take out) are pre-tax. It's basically 100% tax free money. Contribute to it and use it whenever you have a health-related expense. Some decent anecdotal examples:

I just bought new frames and glasses and used my HSA. This was pre-tax in its contribution and withdrawal. It thus cost me just $110 FLAT to buy these. If I needed to use post-tax money, it would have cost about $150 in actual pre-tax income, then have taxes taken out, to have that much in cash.

Again, I'm big into pre-tax investments as much as possible.

Make sure, however, that you check (a) state laws and (b) your health plan to see if you can access an HSA. Talk to HR about this.

Random Anecdotal Opinion: Because of the above, I actually find myself actually taking care of myself with preventative care. It feels a lot better to go get your physical, go to the dentist, go to the dermatologist, etc. when you are using pre-tax money. This might be one of those mind tricks, but it works for me. Hopefully someone else writes a thread about health/wellness because I could still use a few pointers there.

5. Max IRA: This is tricky because of income levels and tax brackets. If you are in Big Law then skip to #6. If you make less than $71,000 then contribute the max ($5,500) to a traditional IRA. Traditional IRA is better than 401k because there are usually less admnistrative fees and you have a wider variety of funds from which to select.

There is a big debate about contributing to a Roth (post-tax) or Traditional IRA (pre-tax). Google "Roth vs. Traditional IRA" and read about it and select from your personal preferences. All I'll say is that I prefer pre-tax investing because I anticipate paying little to almost no taxes in retirement.

6. Max 401k: Max your 401k up to the full $18,000 (if you can). I personally find this to be a great way of saving because the money is taken directly from your paycheck, put into your 401k, and then it's relatively hard to get. Do this.

7. Pay Off Lower Debts: This is disputable with #8, but I'd pay off lower debts next. Paying off a debt with a 3-4% interest rate means you are getting an automatic rate of return slightly above that number. Reducing debt reduces fixed costs, which you can tell I like.

8. Taxable Brokerage Account: This is last because with contributions invested post-tax, the gains (i.e., the amount earned on the investments) are taxed as capital gains. But even with this, you are better off investing than leaving too much money on the side (i.e., uninvested).

IV. A Brief Word on Marginal Taxes

Taxes Are Marginal: A lot of people screw this up. Taxes are marginal. This means that your tax rate is the percentage of tax applied to your income for each tax bracket in which you qualify. It breaks down like so:

In word terms, this means that income between $0 and $9,275 is taxed at 10%. Income between $9,276 and $37,650 is taxed at 15%. And so on.

You want to contribute to pre-tax accounts so you can lower your AGI and thus lower your tax burden.

Easy example: You make $160k in Big Law. The last $18,000 of that is taxed at 28%. Contribute all of that money to a 401k instead and boom, you have all $18,000 of that money invested; conversely, if you invested none of that, $5,040 would have been taxed, and you go home with $12,960. That sucks. Invest the whole damn thing and win.

Note that some people confuse this whole "marginal tax" thing. They think, "If I go from $75k income to $100k, now I'm in the 28% tax bracket and I'll make less." Now you can look at them and laugh because you read on the internet that this is complete bullshit. Almost all of the income will be taxed the same, just the income from $91k to $100k will be taxed at 28%. And if you contribute to your 401k, you will avoid that higher marginal tax rate! BOOM!

V. Investing

Invest in Stocks, They Always Go Up: This might catch some flack, but given a long enough time horizon, stocks always go up. All the noise you hear about the market is complete and total bullshit. There's a really important saying you must burn into your brain: time in the market beats timing the market. See below.

This is one of my favorite articles ever--what would happen to a guy who always invested at market peaks (i.e., pre-collapse): http://ritholtz.com/wp-content/uploads/ ... e-1900.png.

Point is that you should always just continuously invest. Do not pull out of the market just because of a recession--look at the chart above, the market always comes back up (just as it did after 2008, just as it did after the mini-bear blip early in 2016).

You should be 90/10 (or maybe 100) percent in stocks/bonds until you are about five years from retirement. Then it might be time to see an adviser.

Invest Passively in Index Funds: An index fund is a fund that tracks an index and nothing else (e.g., the Dow, the NYSE, the S&P 500). Do this for several reasons:

1. These are extremely low cost. Costs are important. Costs kill your returns in the long run.

2. You cannot beat the average. People get paid hundreds of thousands of dollars per year as their full time job, and they usually don't beat the market.

This is anecdotal, but given it's the new year, check this out: http://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/04/upsho ... ctionfront

TL;DR: none of the professional's "stocks to buy in 2016" beat the market. You can't beat it either. It's okay to have, say, 5-10% of your money as "haha I'm gonna play with stocks," but any more than that is dumb.

Costs Are Super Important: Index funds have super low costs. Let's look at an example:

Fund A: an actively managed fund that gets 8% returns (better than the market average) but has a 1.75% expense ratio. If you invest $10,000 per year for 30 years, minus fees, you end up with $877k.

Fund B: a passive index fund with 7% returns (market average), with an expense ratio of .05% (which is what mine is). If you invest $10,000 per year for 30 years, minus fees, you end up with $1.01M.

Thus, even if Fund A did better, because of its fees, it ate up more than $125k in returns. This is because fees compound just like returns do.

But wait, there's more. This hypothetical assumed that actively managed Fund A outperformed the market average over 30 years--this does not happen at a rate of about 98% of the time when it comes to active vs. passive funds. In other words, 98 out of 100 active funds fail to beat passive funds over the course of 30 years.

Thus, Fund A, at best, likely had 7% (average) returns, but subtract costs and you have $730k. Now you've lost a quarter million because of fees.

Fees, over time, kill performance. Avoid them, and because of this same principle, avoid financial advisers (unless you have a crazy complicated financial situation, which, in that case, hire a fee only financial adviser that is a fiduciary).

Time in the Market Beats Timing the Market: I'm going to repeat this for emphasis: invest as long as you can, because compound interest is awesome. Let's look at another example.

Person A graduates law school and, at age 25, begins investing $15,000 per year for 20 years (contributions total $300,000). He stops contributions at age 45 (for whatever reason) and lets his money grow to age 60 without withdrawing any funds. Assuming 7% returns, Person A has $1.8M at age 60.

Person B graduates law school and lives the dream, but does not contribute until age 35. He then contributes $18,000 per year from age 35 to 60 (contributions total $450,000). Despite investing substantially more, and again assuming 7% returns, Person B has $1.1M at age 60.

Rules to Remember: Contribute as early and as much as possible. Reinvest your dividends. Invest in low cost index funds. Invest mostly in stocks.

Additional Reading on Investing:

http://jlcollinsnh.com/stock-series/

https://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/Boglehe ... philosophy

VI. Contributing to Your 401k

Basics: A lot of this is covered in the investing section above, but if you're in Big Law, I can't imagine not contributing all $18k to my 401k. I make 1/3 of Big Law salary and contribute the full $18k--you can too (if you lower your fixed expenses enough).

Within your 401k, select index funds with low expense ratios. I'd recommend the S&P 500 index, which tracks the 500 biggest companies in the U.S. Some suggest investing in international indexes, but I agree with John Bogle that American companies have international exposure and thus ebb and flow with those markets anyway.

Always Roll Over Your 401k: You will likely switch jobs within five years. Never, ever, cash this money out (unless you are in a dire emergency). See "time in the market" principle.

VII. Pay Off Debt or Invest?

This is Likely Personal: This is a super tricky topic that deserves its own article. Before getting into my belief, just note that personal finance is personal. Some people (me) are totally okay with debt, others despise it and want to get rid of it. You do you.

Focus on the Interest Rate: The number one factor to consider in whether to pay off debt or invest is what interest rate your debt is. Always remember as a baseline that the stock market has returned (over the long run) about 7% after inflation. If your debt is much lower than this (3-4%), let the debt ride and invest, because your investments, over the long term (and with the power of compound interest) will beat the "returns" of paying off lower interest debt.

Conversely, if it's high interest debt (e.g., a credit car with 18% interest), get rid of that ASAP. That is terrible debt and investing will never beat this type of debt. Note that you should contribute to your 401k before paying off this debt, because 401k up to your company's match is a 100% return, which beats the interest rate on your debt.

Student Loans: Note here, and I'll discuss below, that student loans are different due to income driven repayment plans. This makes the interest rate on student loans borderline fake. You really need to do a case by case analysis.

VIII. Student Loans

Get on An Income Driven Repayment Plan: I don't care whether you're in small law (me) or big law, get on REPAYE. Its provisions include allowing your payments to go to $0 if hardship arises. This is basically student loan insurance.

Don't Refinance Unless You're Sure You Will Pay Them Off Soon: Refinancing takes away the above insurance. It also usually involves a co-signer, which means that if you die, they can go after your spouse. Not good. Again, federal loans have built in insurance-type protections in them. This makes their slightly higher rates worth it.

Gaming Student Loans: This is a borderline fetish topic for me because I've looked into it almost a laughable amount. But basically, if you make low income, get on REPAYE, intentionally lower AGI, and never plan on repaying your loans back in full. You will almost certainly pay less if the numbers work out right (e.g., lower income, high debt; or even high income with a lot of contributions reducing AGI). This is complicated, and deserves an entirely separate post, but make sure you look into REPAYE before becoming one of those people who makes paying off loans a higher priority than sex.

IX. Save for Retirement--It's Easier and Cheaper Than You Think

This is Personal!: What you are about to read is my own thoughts on retirement. But basically, as you'll see, I'm aiming for a modest standard of living so I can retire early, because I value time and I don't really aspire for material/costly stuff--I don't really care about having a huge house, a Mercedes, sending my kids to private school, etc. It's just not important to me. Of course, some of you went to elite undergrad and elite law schools and now are in big law so you can aim higher than that. This is perfectly fine. You're not wrong, I'm not right. Just know that your standard of living and current spending drastically affects if and when you can retire.

Money Buys Time: I could go on a long rant here, but money can be used as a utility for one of two things: (1) to buy stuff (houses, cars, food, etc.) or (2) time (a retirement fund). I personally place higher utility in time, not consumerist stuff. Read "Your Money or Your Life" for more on this.

How Much Do You Need: This is perhaps the dumbest thing going in mainstream personal finance. Professionals who do finance for a living honest to God think that $2M isn't enough. That's laughable.

Here's the key: assuming no income (social security, retirement hobby, etc.), you need 25 times your yearly expenses to retire. I conservatively project that my fiance and will spend about $48,000 per year (assumes a paid off mortgage), meaning we need $1.2M to retire. Because we are maxing our accounts, I think we will get there at age 42-45.

If you think this isn't a lot, go read Mr. Money Mustache--he retired in $625,000 and is killing it because his expenses are so damn low.

Where Does 25x Expense Come From?: This number comes from the fact that, statistically speaking, if you only pull 4% from your retirement accounts, they will last forever. This is because, over time, stocks go up at 7%, inflation goes up by 3% (and thus eats 3% of returns), leaving you with a gap of 4% to spend reliably, forever. That's oversimplified, but I'll point you to this article: http://www.mrmoneymustache.com/2012/05/ ... etirement/

Low Fixed Expenses!: I'm going back to where I started. The lower your fixed expenses, the less you need for retirement. If you do what most people do--buy a huge house, buy nice new cars every 4-5 years, spend a lot of money on random stuff, etc.--then you do in fact need millions to retire. But if you're smart with your money and avoid lifestyle inflation, you will retire very quickly.Ideally, you want to retire in a time of low stock prices, just before a long boom. But you can’t predict these things in advance. So again, how do we find the right answer?

Luckily, various Early Retirement Ninjas have done the work for us. They analyzed what would have happened for a hypothetical person who spent 30 years in retirement between the years 1925-1955. then 1926-1956, 1927-1957, and so on. They gave this imaginary retiree a mixture of 50% stocks and 50% 5-year US government bonds, a fairly sensible asset allocation. Then they forced the retiree to spend an ever-increasing amount of his portfolio each year, starting with an initial percentage, then indexed automatically to inflation as defined by the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

This gigantic series of calculations was called the Trinity Study, and since then it has been updated, tweaked, and reported on, recently by a guy named Wade Pfau. He created the following very useful chart showing what the maximum safe withdrawal rate would have been for various retirement years:

As you can see, the 4% value is actually somewhat of a worst-case scenario in the 65 year period covered in the study. In many years, retirees could have spent 5% or more of their savings each year, and still ended up with a growing surplus.

This brings me to a critical point: this study defines “success” as not going broke during a 30-year test period. To people like you and me who will enjoy 60-year retirements, that would not be successful – we want our money to last much longer than 30 years. Luckily, the math in this case is pretty interesting: there is very little difference between a 30-year period, and an infinite year period, when determining how long your money will last. It’s much like a 30-year mortgage, where almost all of your payment is interest. Drop your payment by just $199 per month, and suddenly you’ve got a thousand-year mortgage that will literally take you 1000 years to pay off. Increase the payment by a few hundred, and you have a fifteen year payoff! In other words, above 30 years, the length of your retirement barely affects the safe withdrawal rate calculations.

The following graphic shows the power of savings rate--the higher percentage of income you save (savings rate), the less years you need to work:

Important Note: If you want a higher standard of living in retirement, that's fine! Go for it! This is a purely personal value trade-off in which you are basically agreeing to work more to have a higher standard of living in retirement. That is an entirely okay decision and is a completely rational trade-off to make. So long as you are aware of this when you are making big decisions (e.g., buying an expensive car, an expensive house, etc.), you will go a long way in knowing how much you are going to need for retirement.

If You're in Big Law--Save Like Crazy: I don't have the stomach for Big Law, but God I wish I did. With spousal income I'd save $125k per year. You would have close to $2M after 10 years. That's plenty to retire on if you're smart.

Retirement Does Not Mean Not Working: There is a societal retirement police. You are supposed to retire at a certain time, with a certain amount of money, at a certain stage of your life, and damnit you better not work AT ALL during retirement. All of this, much like other societal norms, is complete and total bullshit (this has to be the 10th time I've said that this post...who cares...emphasis matters).

I personally plan to "retire" at age 42-45. If I haven't started a solo practice by then, I might try that. I also might try to become a mediator and try to mediate 10-20 cases per year for some income. I'd also like to become a coordinator for a local high school football team (serious).

The better term here, I guess, is financial independence, or what some call fuck you money--having enough money so you can do whatever the hell you want with your time. This seems extremely ideal to me, so I'm aiming for it as soon as possible.

How to Access Money: You likely notice I discussed contributing mostly to retirement accounts, which you usually can't pull from until you are 59.5. Some might ask, "How do I get the money?" This is more complicated than intended for this post, but google Roth IRA conversion ladder, 72(t) distributions, and other ways to get this money. It's definitely advanced but it's possible.

X. Conclusion and Further Reading

This got pretty anecdotal towards the end, but I'm at work and a 30 minute lunch break turned into a two hour post. I know some people will disagree with my personal opinions, but I hope the value provided here outweighs any of that. Overall, to summarize what I think is universal advice:

1. Have an emergency fund of 3-6 months of expenses;

2. Follow the hierarchy of where your money should go;

3. Invest in low cost index funds;

4. Save as much as possible;

5. Make choices that parallel your personal comforts re finances (e.g., comfort with debt);

6. Understand that higher cost of living = you need more to retire; and

7. Educate yourself.

Personal finance and accumulating wealth is fun, and admittedly nothing I'm saying is really original--most of it is from years of reading blogs, r/personalfinance, r/financialindependence, and forums at Bogleheads and Mr. Money Mustache. I'd recommend the following:

Books

1. I Will Teach You to be Rich (https://www.amazon.com/Will-Teach-You-B ... o+be+reach)

2. Your Money or Your Life (https://www.amazon.com/Your-Money-Life- ... 6MGKDSFXCR)

3. Bogleheads' Guide to Investing -- good shit on insurance, other adult shit (https://www.amazon.com/Bogleheads-Guide ... 2QZZMTTGA1)

4. The Little Book of Common Sense Investing (https://www.amazon.com/Little-Book-Comm ... ME3FQGE8SB)

5. A Random Walk Down Wall Street (https://www.amazon.com/Random-Walk-Down ... JZH5D32HRT)

Websites

1. http://www.iwillteachyoutoberich.com/blog/

2. http://www.mrmoneymustache.com/ (A very alternative viewpoint to mainstream personal finance)

3. https://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/Main_Page

Cheers.